Unsupervised Learning for Physical Interaction through Video Prediction

July 9, 2018

TL’DR:

Instead of trying to directly predict the raw pixel values for the next frame or even the difference from the previous frame, the authors of [1] propose 3 models (DNA, CDNA, STP) that predict the motion of each image part and apply it to the corresponding region of the last frame since appearance information is available therein. Consequently, the models learn to disentangle appearance from motion and are (partially) invariant to appearance, being able to predict multiple timesteps ahead.

Models

According to Wikipedia, advection is the transport by bulk motion of a substance whose properties are carried with it. To be honest, I didn’t know the meaning of the word until reading this paper, so after looking up I found it a spot-on name choice as it expresses that the object’s (visual) properties (i.e.: color, shape, texture) are preserved during the (predicted) motion.

Core Architecture

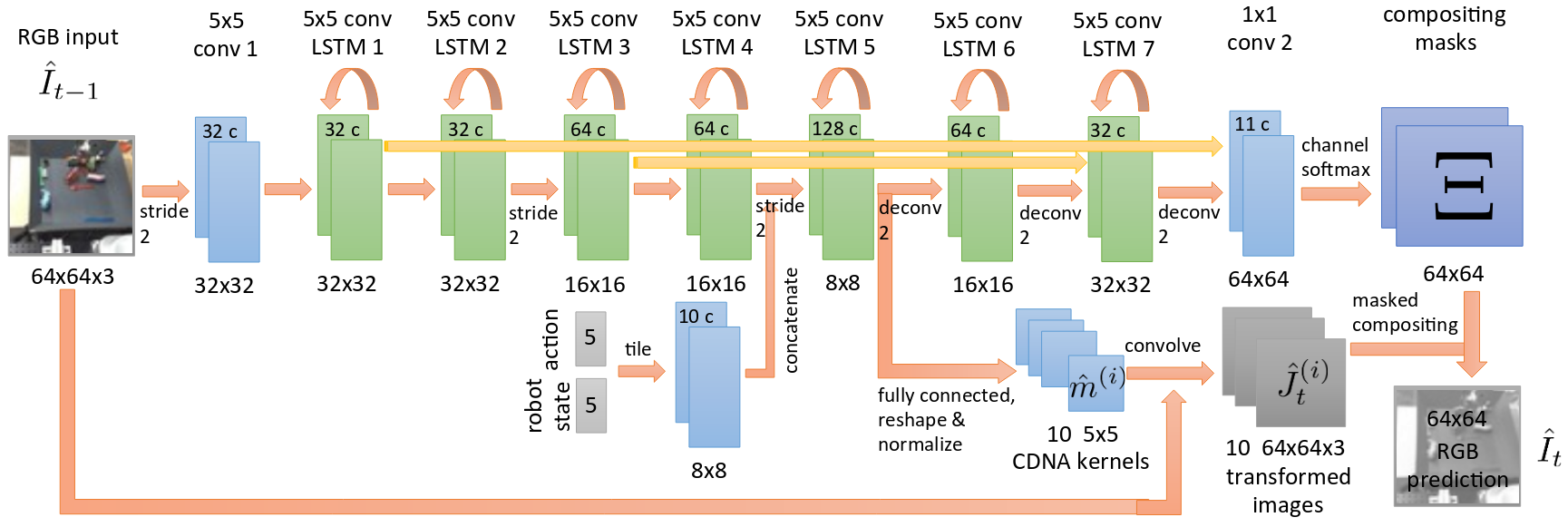

The core of all approaches consists of an encoder-decoder structure of convolutional layers intervened with convolutional LSTM units [2], which account for the nature of video sequences. On top of that, there are forward skip-connections that help preserve high-resolution information.

The greatest insight of this work is realizing that predicting objects’ motion without attempting to reconstruct their appearance (either directly or by the difference between frames) allows the model to better disentangle appearance from motion, which in turn enhances performance. Moreover, Chelsea Finn and colleagues verify that action-conditioned frame prediction, that is, integrating the agent’s actions and internal state to the architecture, also improves results.

Prediction Modules

DNA – Dynamic Neural Advection

The model generates one motion matrix for each pixel of the frame. Thus, it computes the prediction of each new pixel value as the dot product between the corresponding motion matrix and the region around such pixel. The authors explain the motion matrix as a distribution over locations and the new pixel value as the expected value of the distribution, this is an interesting (and cool) view. Wouldn’t you rather say your model outputs a distribution over locations whose expectation will be the new value than say it outputs an ordinary matrix and computes the dot product?

Assuming spatial locality over the frames across each timestep, and that pixels will not move large distances, the size of such motion matrices can be small, which considerably reduces the problem’s dimension.

CDNA – Convolutional DNA

Further assuming that different regions of the image may present the same motion (e.g., a car on a street), the per pixel matrix can be replaced by kernels whose weights are shared throughout the whole image. Then, it suffices to predict only a few (i.e., 10) matrices, instead of $H \times W$ (i.e., 4096). Additionally, the model generates one (soft) mask per motion matrix so that it can stitch everything together by selecting how much of each motion matrix goes into the prediction of each pixel.

This approach reduces in nearly 90% the number of values produced by the network.

The authors also include one extra “background” mask which simply copies the values of the previous frame into the prediction. Such mask typically acts on background regions where there is no movement, hence the name. Likewise, the DNA (above) and STP (below) modules have this mask.

STP – Spatial Transformer Predictors

Instead of producing values for the motion matrices as CDNA, this model outputs a set of parameters that are fed to a Spatial Transformer Network (STN) [3]. Hence, the model’s name. The transformations are modelled as 2D affine (translation, rotation, anisotropic scaling, skewing) and aim to warp the previous image pixels onto the future pixels.

Experiments

The authors introduce a new dataset, named BAIR Robot Pushing dataset, consisting of sequences of robotic arms pushing different objects in bins, the corresponding gripper poses (internal states) and their commands (actions). Besides evaluating on this new dataset, they also study the proposed architectures on the Human3.6M dataset [4], which consists of humans performing various actions in a room.

Finn and collaborators verify that modeling pixel motion outperforms directly predicting pixel values or even the difference between previous and current frames. Not only that but such gap enlarges when dealing with novel objects. Furthermore, training for longer horizons and conditioning on the action/state of the robot enhance performance.

From left to right: groundtruth, CDNA, ConvLSTM with skip, FF multiscale [5], FC LSTM [6]

Their models also surpass prior methods on Human3.6M. Still, after 10 timesteps (time span it was trained to predict), it starts to degrade. Note that each frame is a timestep and corresponds to 1 second due to temporal subsampling.

Degradation over time is natural and comes from future’s inherent uncertainty. As the models are trained with $\ell_2$ norm, uncertainty translates to blur. If the model thinks there’s a 50/50 chance that the object is going to be either in position A or B, then it depicts the object in both positions simultaneously but halves the pixel intensity of each.

Although the DNA model is more flexible, the CDNA and STP ones are more efficient. Indeed, the latter architectures learn to mask out objects that are moving in consistent direction as shown below.

All three models have similar results on the robot pushing dataset, specially when dealing with novel objects. However, for the held-out subject in Human3.6M, the CDNA has worse performance than the other two.

Observations

Since prediction comes from applying a transformation directly to the present frame, the model is fated to get image boundaries incorrectly. Moreover, if the object part is occluded, it cannot be predicted by combining nearby pixels. In order to address this issue, the authors (in the CDNA and STP models) generate raw pixel value predictions from the last LSTM cell, which is stitched together with the other predictions by its corresponding mask.

An interesting way to handle occlusions, at least for known objects, is by introducing a long range feedback skip connection. Thus, allowing long term memory and higher level concepts back to bottom layers, which may help to predict occluded or even not yet seen parts of known objects.

It seems to me, by inspecting the code, that the CDNA approach runs short of a mask at the end. It generates 10 different transformation matrices plus the generated raw pixel values while it outputs only 11 masks and 1 is already used as the background mask (i.e., it copies the values from the previous frame).

Useful links

References

[1] Chelsea Finn, Ian Goodfellow, and Sergey Levine. “Unsupervised learning for physical interaction through video prediction”. Advances in neural information processing systems (NIPS), 2016.

[2] Xingjian Shi, Zhourong Chen, Hao Wang, Dit-Yan Yeung, Wai-Kin Wong, and Wang-chun Woo. “Convolutional LSTM network: A machine learning approach for precipitation nowcasting”. Advances in neural information processing systems (NIPS), 2015.

[3] Max Jaderberg, Karen Simonyan, and Andrew Zisserman. “Spatial transformer networks.” Advances in neural information processing systems (NIPS), 2015.

[4] Catalin Ionescu, Dragos Papava, and Vlad Olaru. “Human3.6m: Large scale datasets and predictive methods for 3d human sensing in natural environments.” IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence (PAMI), 2014.

[5] Sascha Lange, Martin Riedmiller, and Arne. Voigtlander. “Autonomous reinforcement learning on raw visual input data in a real world application”. International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN) , 2012.

[6] Michael Mathieu, Camille Couprie, and Yann LeCun. “Deep multi-scale video prediction beyond mean square error”. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2016